On Thursday, May 18, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its first major opinion on fair use in copyright in almost 30 years. In Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, the Court was asked to determine whether the Andy Warhol Foundation’s (AWF) licensing of one of Warhol’s prints of the legendary musician Prince Rogers Nelson, based on a photograph by Lynn Goldsmith, to use as a magazine cover was a fair use under copyright law. The Court grappled with the question of when a copyright holder’s right to “transform” their works into derivative works is impinged by artists who recycle copyrighted works into new art. In a 7-2 decision, the justices held that the Foundation’s licensing activities were not a fair use of Goldsmith’s copyrighted work.

Lynn Goldsmith is an established celebrity photographer who made a career of licensing her photographs to magazines and news outlets. In 1981, Goldsmith was hired by Newsweek to photograph the then up-and-coming musical artist Prince for use in an article about the musician. A few years later, Vanity Fair obtained a license from Goldsmith to use one of the photographs from her session with Prince as a reference work for another artist to create a new work for a magazine cover. That artist was Andy Warhol.

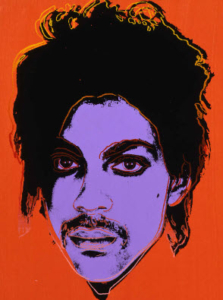

In 2016, Vanity Fair’s publisher Condé Nast returned to AWF seeking to license the same image for a special tribute edition after Prince’s untimely death. AWF informed Condé Nast that it no longer had that image, but it had other images of Prince by Warhol that it could offer. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol had created fifteen other versions of the Prince print based on her photograph, which had not been sold or licensed in Warhol’s lifetime. AWF offered one of these alternate versions, known as “Orange Prince,” for use on the magazine cover. When Goldsmith saw the unauthorized work based on her photograph, she contacted AWF claiming that the cover infringed her copyright in her photo. AWF responded by suing Goldsmith for a declaration that its use was not infringing. AWF asserted that Warhol had “transformed” the original image into a new work, and therefore its use of Warhol’s print was a fair use.

What Is Fair Use?

Under U.S. law, a copyright holder has the exclusive right to exploit a copyrighted work in certain ways, such as copying or publicly displaying the work. Copyright owners also have the exclusive right to

prepare “derivative” works based on the copyrighted work. A derivative work is a work that adapts or transforms the original work in some way. Typical examples of derivative works include translations of books, film adaptations of plays, or musicals based on the songs of a famous band. In general, using a copyrighted work without the owner’s permission is copyright infringement.

But not every unauthorized use of a copyrighted work is considered infringement. Copyright law identifies certain uses as “fair uses” of a copyrighted work—for example, reproducing parts of the work in commentary or criticism of the work, in news reporting, or for research or education. These uses are not infringement. One factor courts look at in deciding whether a use is fair is the “purpose and character” of the use. In other words, is the purpose of the secondary use sufficiently different from the purpose of the original, or does it merely replace the original work? And second, is the secondary use for commercial purposes (e.g., licensing or selling)? When the secondary use is the same as the original and it is used for commercial purposes, courts will usually find the secondary use is not “fair.”

But in 1994, the Supreme Court introduced a new factor into the analysis: whether the secondary use “transforms” the original work by adding “something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” The more transformative a work is, the less important is the commercial use.

What Happened In AWF V. Goldsmith?

AWF claimed that Warhol’s prints “transformed” Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince by imbuing it with new meaning and adding Warhol’s signature style. The Foundation said that Goldsmith’s photo depicted Prince as vulnerable, quiet, and socially awkward, while Warhol made him “larger than life.” Since, according to AWF, Orange Prince was transformative, the “character and purpose” factor should have weighed in AWF’s favor in the fair use analysis.

The Court disagreed. It held that transformativeness was a matter of degree, and not the end of the inquiry. If a work is somewhat transformative, but shares the same purpose as the original, the use is unlikely to be fair without other justification. In this case, both AWF and Goldsmith used the works in the same way: to license them to magazines to depict Prince in articles about Prince. Looking to the letter of the law, the Court expressed concern that putting too much emphasis on the transformative factor risked diminishing the copyright owner’s right to “transform” their work into derivatives. The court noted that authorized derivatives—such as movie sequels and stage adaptations—often substantially change the original work and imbue it with new meaning. But these are not fair uses, because they are exactly the ways in which creators make a living with their art. The Court also worried that permitting Warhol to “transform” a photograph by applying a signature style would favor unauthorized use by famous established artists, creating a kind of “fame privilege” to appropriate copyrighted works. And, since Warhol was not commenting on or criticizing Goldsmith’s photograph, but instead merely used it as the basis for his own expression, AWF needed some additional justification for using Warhol’s image of Prince in exactly the same way Goldsmith used her original photograph. The Court cautioned that the lower courts should not consider an artist’s subjective intent in using a copyrighted work, but instead should perform an objective inquiry into whether the purpose of the secondary use does not replace the original.

What Does This Mean For Me?

It is important to remember that the Court limited its decision only to the transformativeness question, and only to the specific issue of licensing images of celebrities to magazines for articles about celebrities. For example, the Court considered but did not decide whether it would be a transformative use for Warhol to create single copies of the Prince prints and hang them in an art museum, because this is not how Goldsmith used her photographs. Also, the Court did not disturb other uses that are traditionally held to be fair, such as reproducing parts of a work in news reporting, commentary, or criticism about the work, or for educational and/or research purposes. However, the Court appeared to diminish the importance of transformativeness in the fair use analysis. Before this decision, a secondary user could often prevail on a fair use claim by showing that the secondary work was different enough from the first, or that they had a different subjective intent in creating the secondary work. Now, secondary users will have to show that any transformation of the original work fundamentally changes the purpose of the secondary use, or else provide some other justification for using a copyrighted work without permission. It is also important to remember that fair use is only one defense to claims of copyright infringement. The Court’s decision in AWF v. Goldsmith did not alter or eliminate other defenses such as implied licenses, scènes à faire, and the idea-expression distinction.

In sum, it is always best to obtain a copyright owner’s permission before using a copyrighted work for any reason. While some unauthorized uses may be fair use, it can take years of expensive litigation for a court to reach that determination. It is much less costly and better for your reputation to simply obtain a license from a copyright holder or use works in the public domain. If you absolutely must use a copyrighted work and cannot obtain the owner’s permission for some reason, be prepared to thoroughly justify your use by showing why the purpose of the use does not replace uses of the original.